Urban Form, Age/Disability, and Wildfire Evacuations in California

California’s insurance and land use policies, combined with our nation’s economic policies that punish PWDs, drive seniors and PWDs to disproportionately live in fire-prone areas that are difficult to evacuate.

Note: this includes an updated link to the story of Anthony and Justin Mitchell, the father and son who died in the Eaton fire. Apologies for the prior incorrect one.

Hard truths I wish didn't exist

DisabilitYIMBY is my second blog/newsletter adventure. The first one was New Earth Disability (NED), which I started in 2014. NED covered the connection between climate and disability – a horribly under-addressed topic, especially back then. It got noticed by staff at the World Institute on Disability (WID) and soon enough, NED became a formal WID program that I managed for six years. Over the past decade, I’ve worked with an assortment of disability advocates and disaster management professionals on what to do before, during and after emergencies.

Many of those advocates and professionals are working tirelessly right now to address the crisis in Southern California. Disability advocates are also angry and demanding change, especially after news has started coming out about the victims: several had disabilities, including an amputee and his son with cerebral palsy, which is unfortunately a story we hear all too often in disasters. Questions have been raised about evacuation planning and communications – two of the biggest issues with inclusive disaster management – and a common refrain is that those victims likely could’ve lived with proper planning, disaster response, and so on.

The reality, though, is that even the most flawless government disaster response likely couldn’t have saved every life lost in LA County. The winds were too strong; the flames spread too fast; the resources were too limited and dispersed to reach every person that couldn’t evacuate on their own (maintaining and setting up enough resources to do so would be a Herculean task). And if we know anything from the world of disaster management, it’s that people with disabilities (PWDs) will always be disproportionately likely to perish in disasters – especially in fast-moving emergencies like wildfire. We can minimize risks and deaths, and try to do so equitably, but if there are casualties in a fire, it’s reasonable to assume that an outsized share will be PWDs.

The same applies to other groups with Access and Functional Needs (AFN), a loose category that includes seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and folks with little or no English proficiency. We know, for example, that roughly 75% of the lives lost in the Camp Fire that leveled Paradise, CA were seniors; we also know that there is significant overlap between age and disability – partly through higher rates of documented disability among seniors, and partly because many seniors without documented disabilities still have similar needs around transportation and communication. (As far as I know, there is no data on how many Camp Fire victims had disabilities, but the age number is still a useful proxy because of overlap/intersectionality).

It’s a very, very hard truth that there’s only so much disaster responders can do in the moment to save lives and do so equitably. We can minimize risk and disproportionate impact, but this is an issue of harm reduction, not reaching perfection. I wish that weren’t the case.

Government, wildfire and disaster response

There is an understandable conflict between many disability advocates who want better planning and the disaster-management professionals who share hard truths about what – and how much – government can do in emergencies. Vance Taylor, the Chief of Access and Functional Needs in the California Gov.’s Office of Emergency Services, constantly drives home the importance of personal disaster preparedness for everybody, and especially for people with disabilities and other AFN. Of course, the emergency checklist for PWDs is longer than it is for able-bodied folks – you need to add more items to your go bag, find appropriate transportation, maybe coordinate caregiving. This bumps up against the reality that PWDs are disproportionately under-resourced and overstressed already, with some folks forced to have almost no assets simply to keep their benefits. So, when professionals like Taylor say that PWDs need robust personal preparedness plans, many advocates point out it’s a sometimes-impossible task and claim that government should do more.

I repeat: there’s understandable conflict.

So, what exactly could government have done to evacuate PWDs in LA County who needed it? You’d assume that it all comes down to having enough accessible transportation (be it ramp-vans, buses with lifts, or ambulances) that can get to people when they are called. On its face, that seems like an issue of funding and staffing and logistics; it’s also one of society deciding how many emergency resources to keep “on-call” for that occasional, exceptional event. Perhaps LA County could have requested mutual-aid standby transportation from neighboring counties, then positioned vans and ambulances around foothill neighborhoods – a big ask with a wind event that gave little advance warning itself. Even then, I can’t imagine a scenario where everybody would be saved, nor one where people with AFN weren’t a disproportionate share of the victims.

That's ultimately why Taylor and other professionals drive home the need for personal preparedness, and at the very least for immediate evacuations. First responders can do their darndest but it's no guarantee they can reach or save everyone.

Urban form impacts wildfire response

However, fire risk and related evacuations are impacted by California’s urban form, which is itself impacted by policy. And it just so happens we’ve made risk and evacuations worse through decades of bad policy on that front. As M Nolan Gray, author of Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It, wrote in The Atlantic, a combination of misguided home insurance policy and NIMBYism have pushed plenty of Californians to areas with high wildfire risk.

Artificially low premiums have also spurred new housing production in fire-prone regions on the edges of cities like Los Angeles. From 1990 to 2020, California built nearly 1.5 million homes in the wildlife-urban interface, putting millions of residents in the path of wildfires. Policy didn’t just pull Californians into dangerous areas. It also pushed them out of safer ones. Over the past 70 years, zoning has made housing expensive and difficult to build in cities, which are generally more resilient to climate change than any other part of the state.

In many ways, the population of forested hills in the LA region is about capitalizing on views of the ocean and LA’s urban form. But hillside views hold a bigger premium because the region doesn’t have enough towers with views – towers which could be built in safer areas. In many other countries and in a few corners of the US (e.g., Miami and Honolulu), towers dot the waterfront, providing high value apartments and condos to affluent residents. But California’s Coastal Commission plus powerful NIMBYs in high value coastal enclaves have made it impossible to build towers on the coast, leading to development of the hills for those who crave a good view (and have the money to afford one). In Pacific Palisades, for example, lower income folks live/lived in mobile homes near-ish the water while wealthier folks lived largely in the hills; with different zoning, you might have waterfront towers and next to nothing in the hills.

Sprawl, evacuations, age and disability

California’s fire-prone neighborhoods also tend to feature low-density development and/or winding roads – features that delay first responders and raise evacuation dangers further. Sprawl means first responders must drive that much farther to reach the next evacuee; winding hillside roads create more bottlenecks and risks that an insurmountable barrier (e.g., a fallen tree across a roadway) will block the only way in or out. This is a frequent topic of conversation in Berkeley, for example, given the North Berkeley Hills have roughly the same wildfire evacuation score as Paradise, CA did before it burned to the ground.

Pacific Palisades (left) and the North Berkeley Hills (right). Left-hand image description: winding roads with homes traverse a hillside near the Pacific Ocean. Right-hand image description: winding roads and homes in a forested hillside, with more of a grid pattern down low.

And it just so happens that seniors and PWDs are usually over-represented in California’s wildfire danger zones. There are a few causes, roughly:

- The high cost of California’s cities, supercharged by NIMBYism, pushes PWDs (who are disproportionately low income and renters) to outer suburbs and rural areas where housing is cheaper. In California, our rural areas feature plenty of combustible forests while our outer suburbs often bump up against them.

- Seniors seeking cheaper retirements (or semi-retirements) away from urban bustle have sought out – and been sold on – housing in communities like Paradise. Others that are more financially strapped might find themselves even more remote areas.

- On the flipside, rural areas have lost younger adults to the State’s universities and urban job centers, contributing to the age imbalance in places like Shasta County.

- Due to California’s Prop 13, which virtually locks property taxes in place after purchase, many senior homeowners choose to age in single-family homes in the wildland-urban interface rather than seek other housing options. California’s shortage of apartments and condos makes it so there are not enough places those homeowners could easily downsize into, even if they wanted to move. (I covered this a bit in the late December weekly roundup)

- A few more exclusive hillside enclaves, such as the Pacific Palisades hills, have a relatively high share of seniors without a high share of PWDs. My educated guess is those residents are largely wealthier professionals farther along in their careers who built up the money to buy a hillside home; I’d further posit that many might have purchased a waterfront condo instead, if only those towers existed. It’s also safe to say many are slower evacuating the house than they would have been in their younger years, even if they can evacuate on their own and don’t identify as disabled.

Long story short – California’s insurance and land use policies, combined with our nation’s economic policies that punish PWDs, drive seniors and PWDs to disproportionately live in fire-prone areas that are difficult to evacuate. We can and should focus on improved wildfire response and evacuation, but we’ll ultimately be constrained by where people live.

Mapping things out

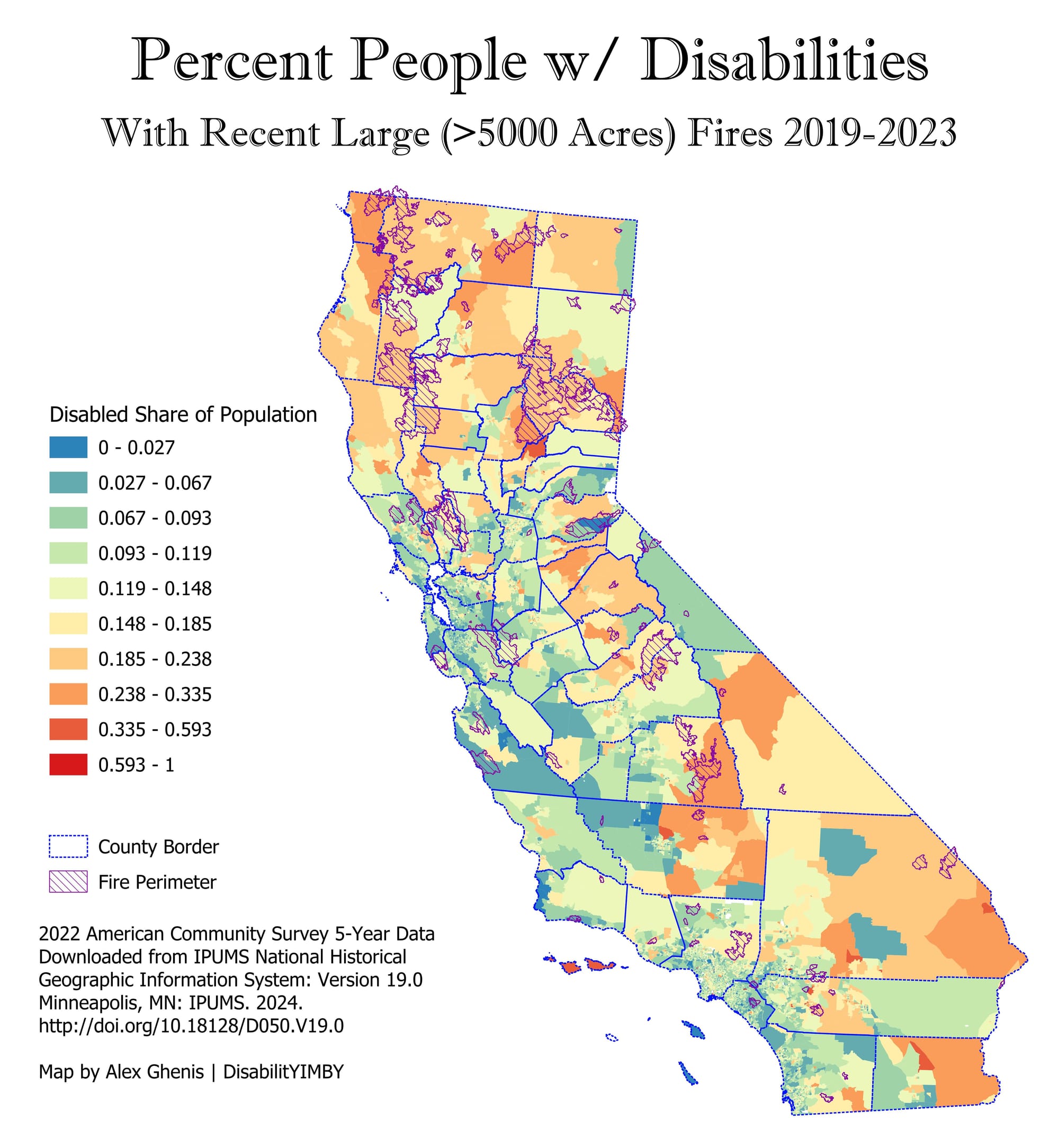

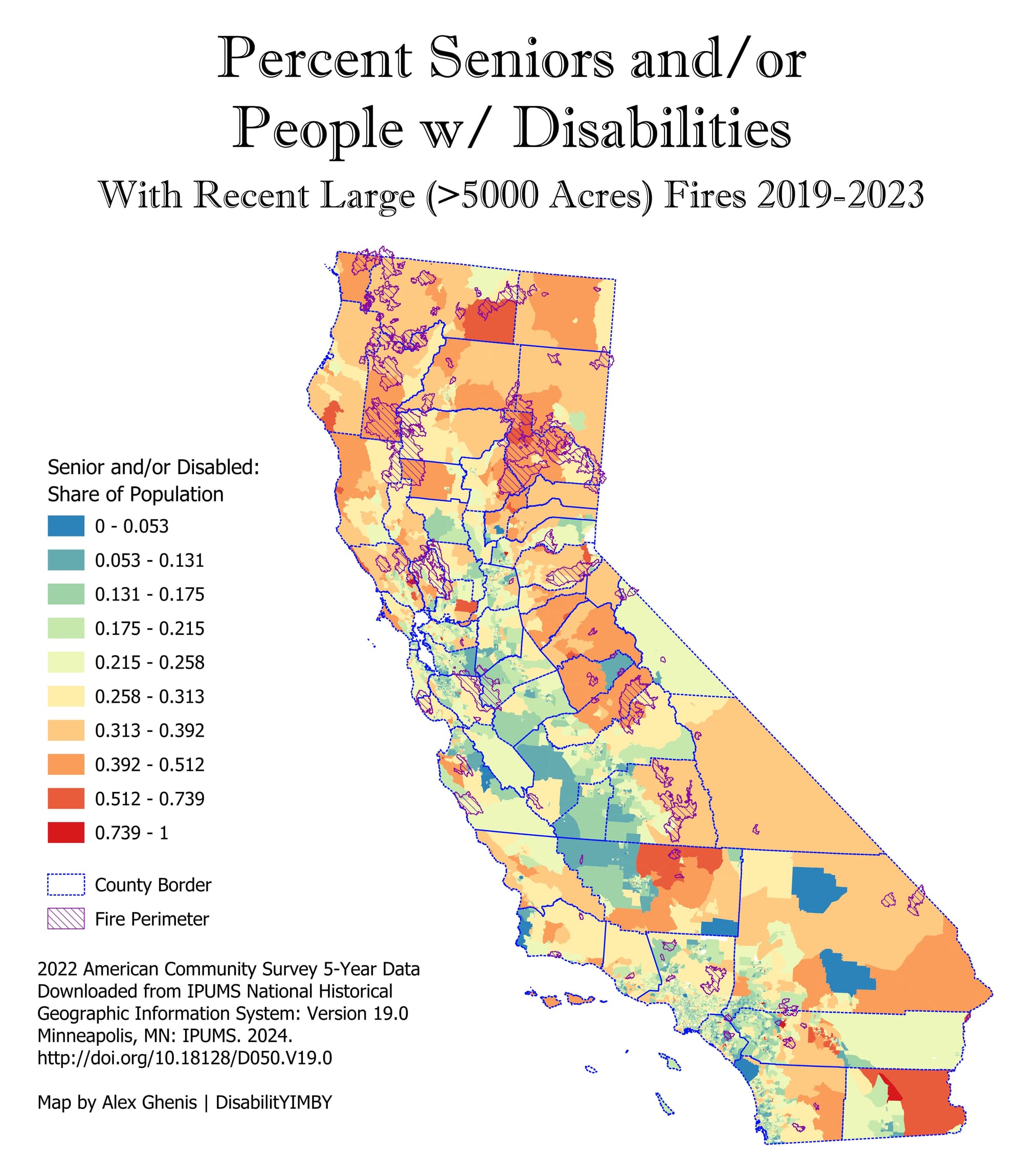

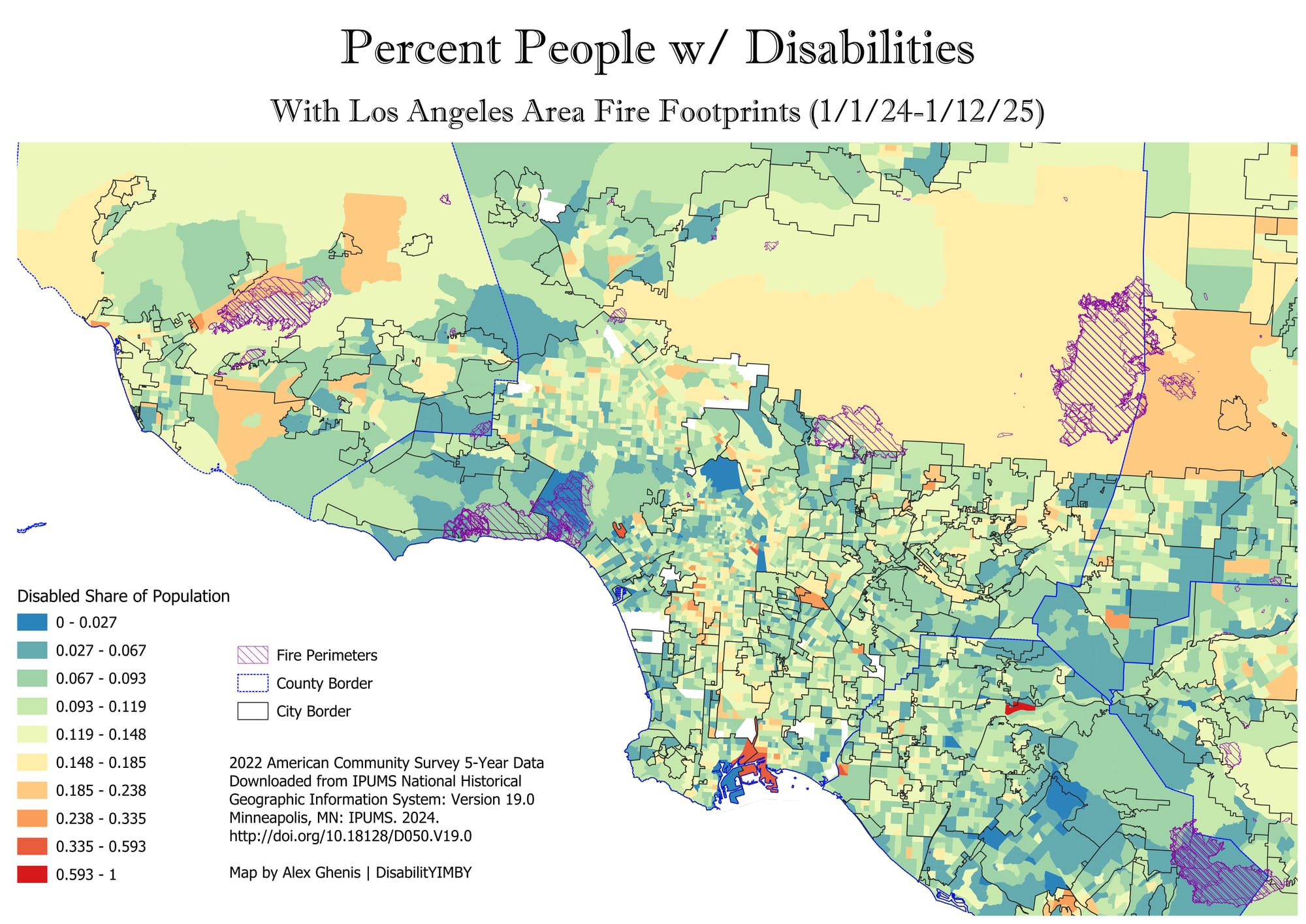

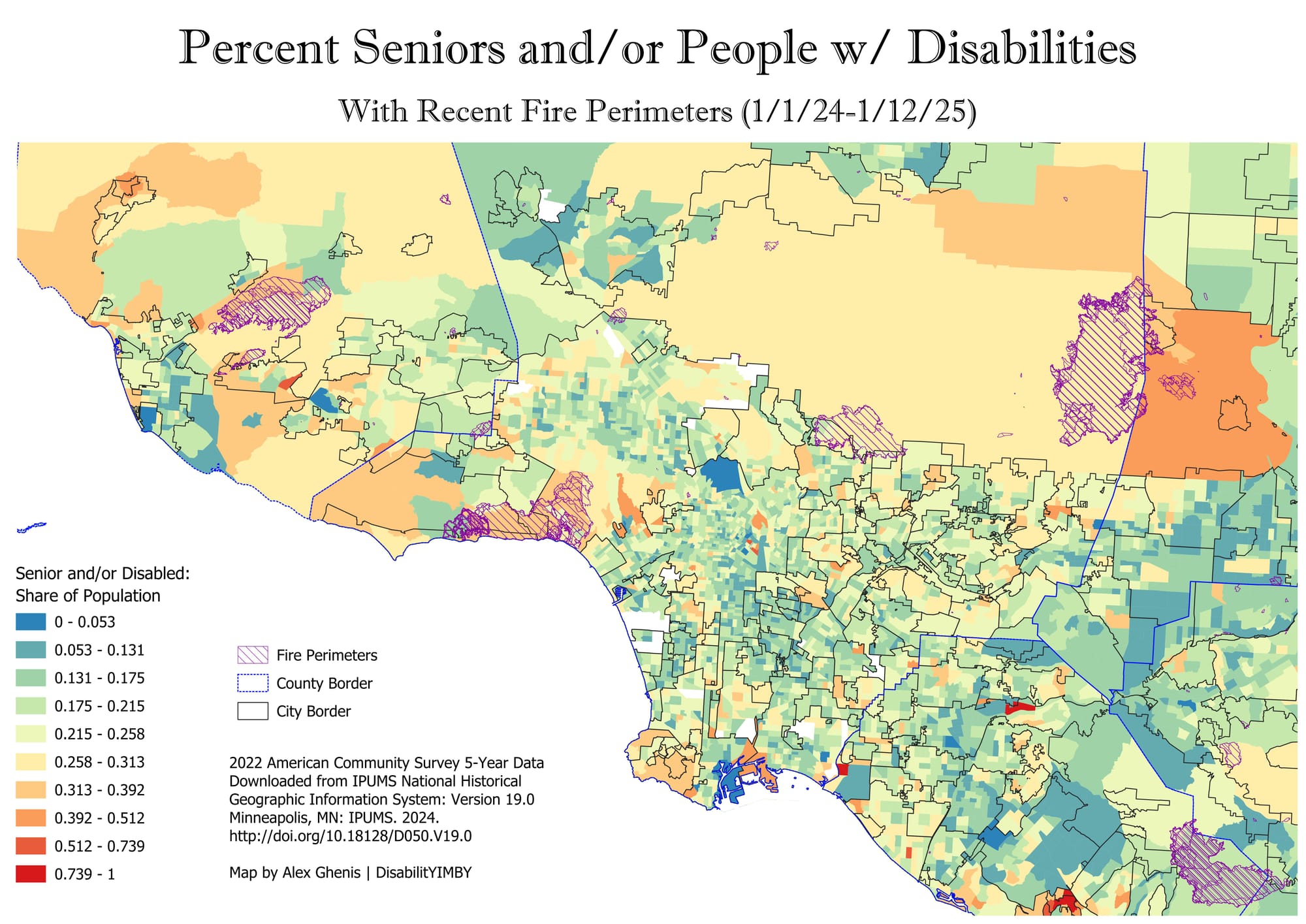

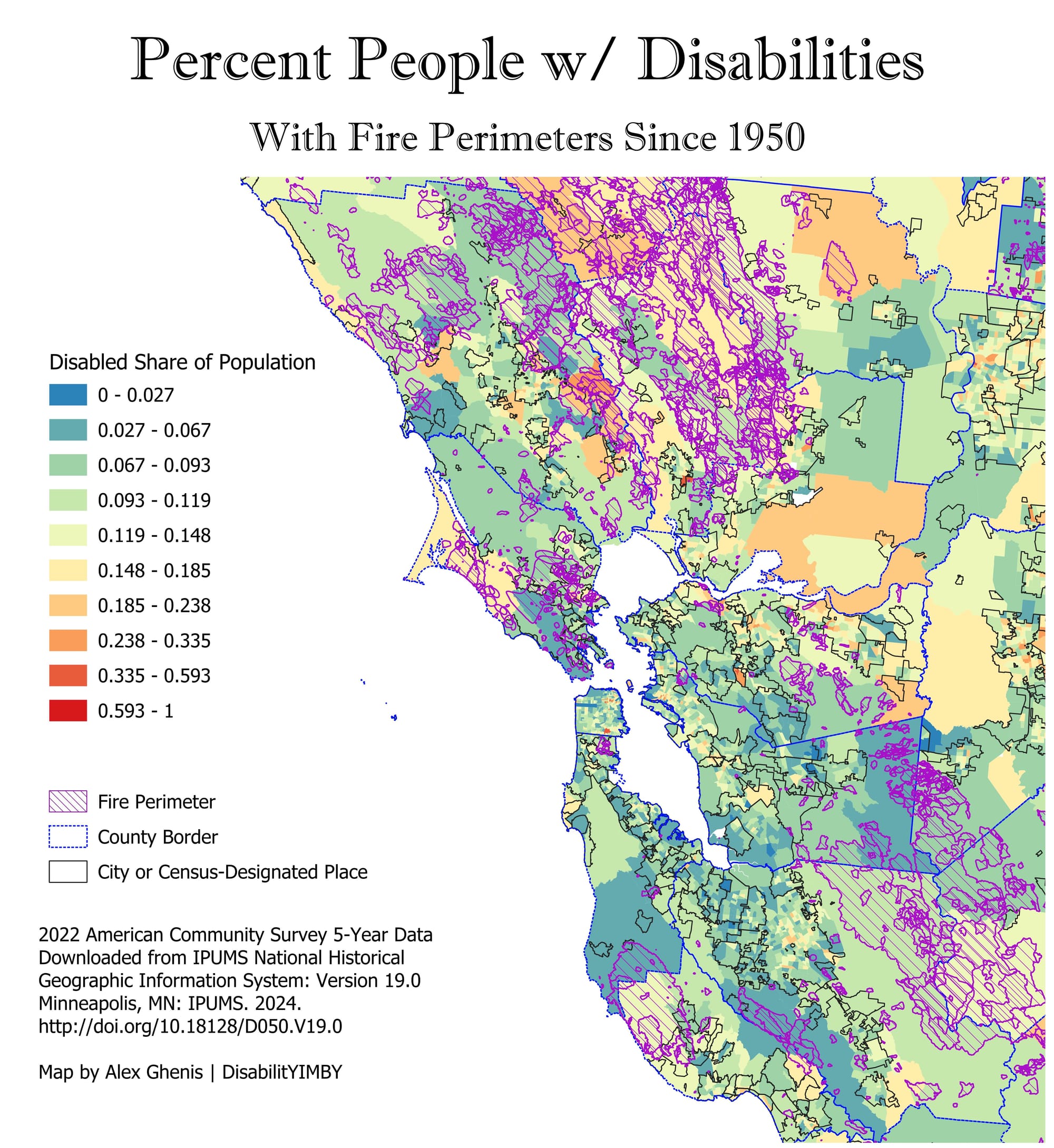

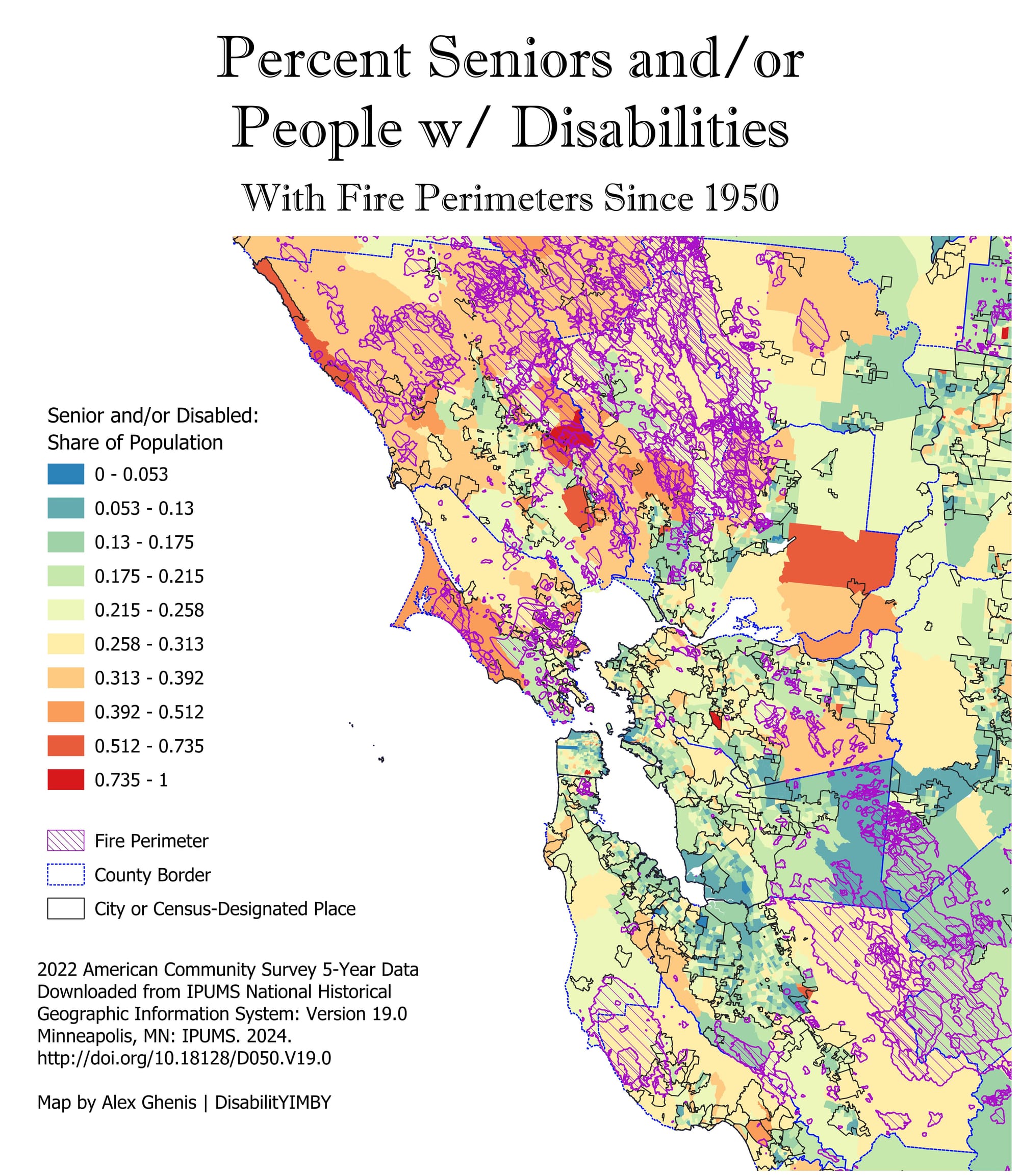

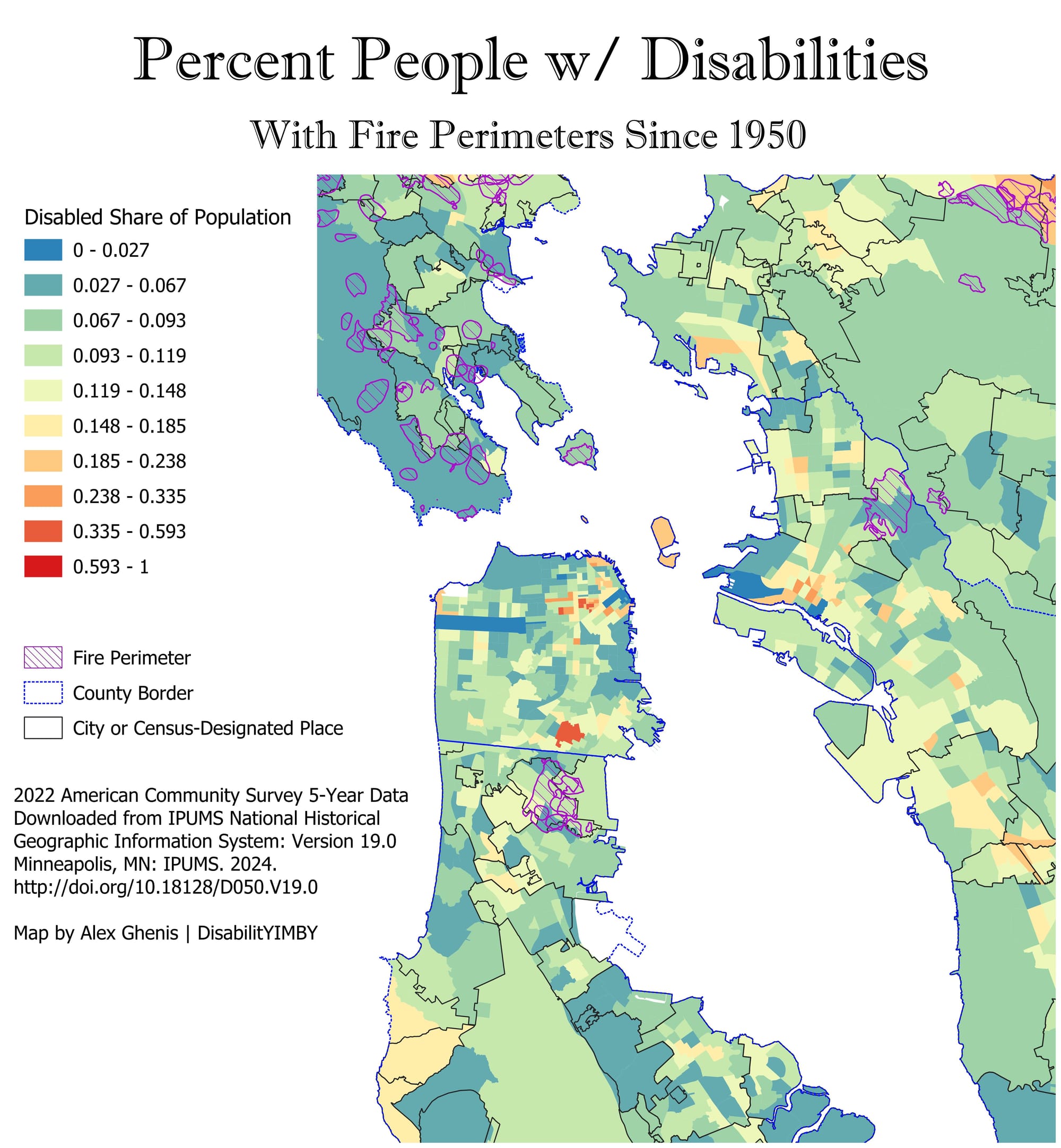

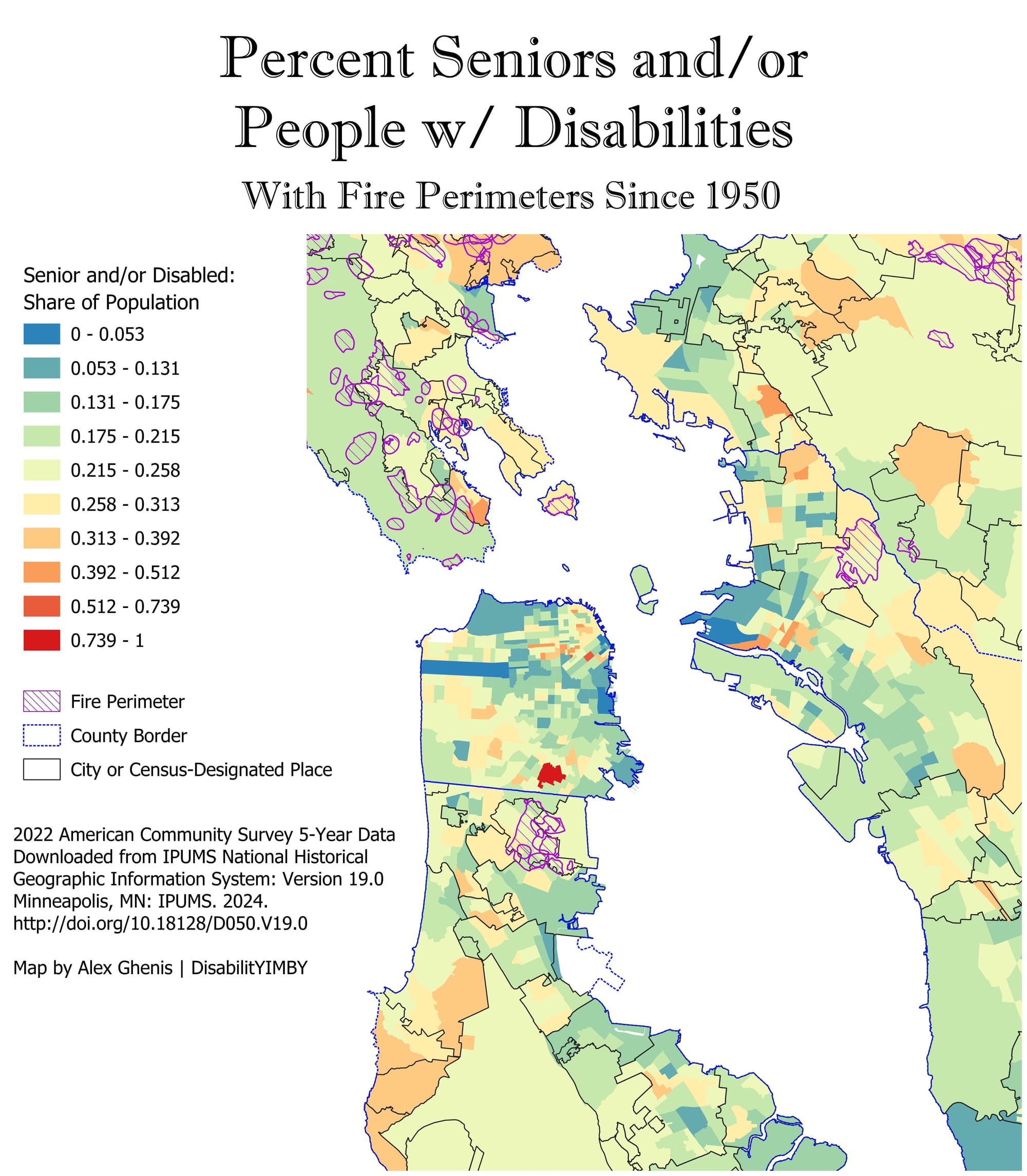

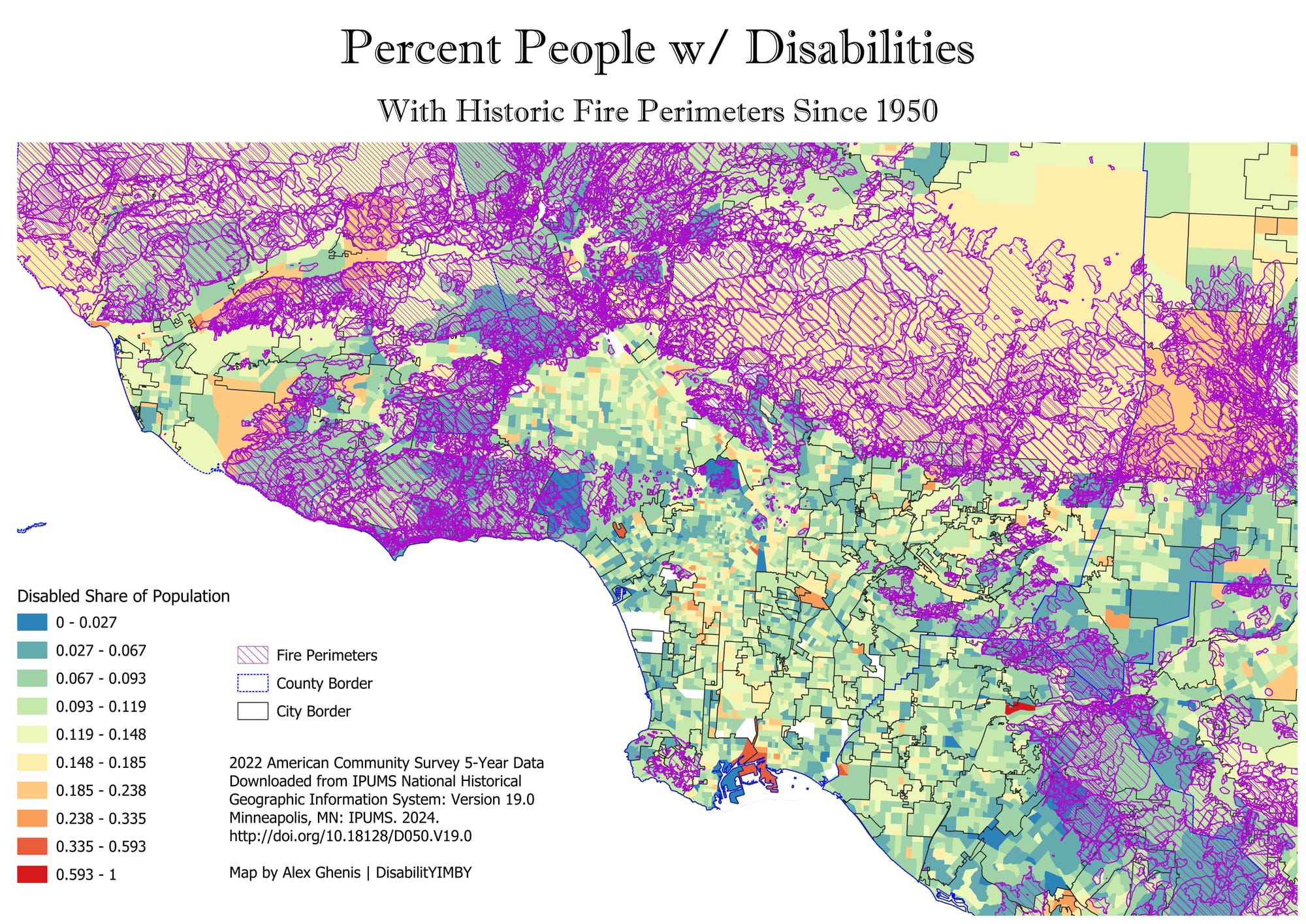

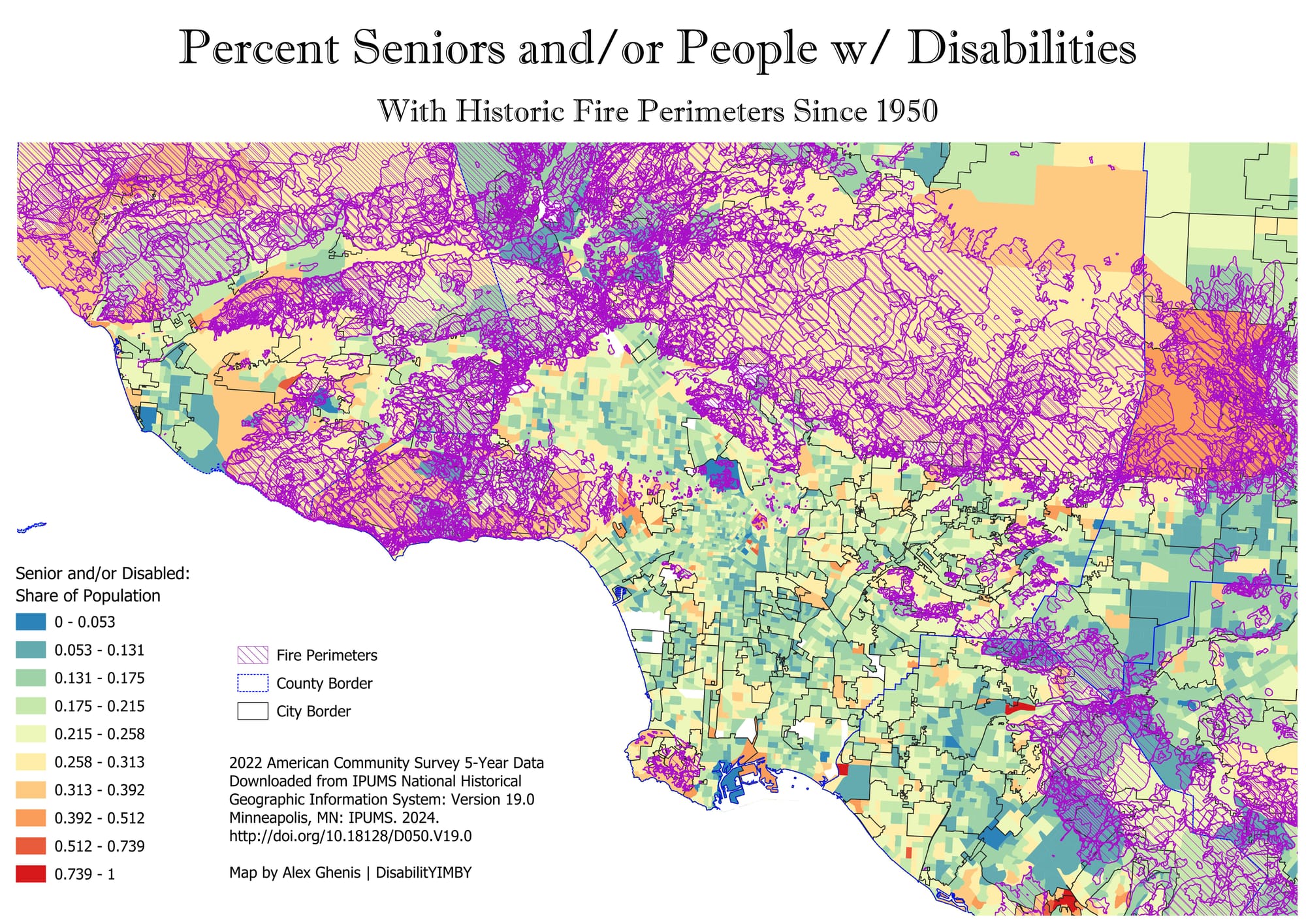

I was curious about where seniors and PWDs live in relation to California’s wildfires, so I spent some time this weekend breaking down the rate of disability and the combined rate of seniors and PWDs (i.e., all PWDs age 0-64, plus all seniors) at the census tract level in California, and compared that to our documented wildfire perimeters.

Map/data notes:

- These maps use American Communities Survey five-year data (so 2018-22 data) sourced from IPUMS NHGIS

- Wildfire perimeter maps are from the CA Natural Resources Agency. Depending on the map, I used historic wildfire perimeters since 1950, large (>5000 acres) wildfires from 2019-2023, and all wildfires from January 2024 through 1/12/2025.

- For comparison, the rate of disability in California is 11.0% and the combined rate of seniors and PWDs is 20.8%

- The map legends in this post break down all CA census tracts to “natural breaks,” or Jenks, which better shows outlier data.

- I've created a Google folder for all the maps in this post (and more), plus another set of maps that break census tracts into deciles instead of Jenks. Please reference this blog if you'll reuse them!

Findings:

(Note: I'm using the below paragraphs combined with image captions to basically do alt-text for these images, since Ghost's gallery function doesn't allow for alt-text. If you would like me to explain any map in more depth, please reach out here.)

At a statewide level, there’s a very clear, high concentration of PWDs in far Northern California and in some parts of the central and southern Sierras, which is also where many of our largest recent fires have been; the combination of seniors and PWDs is also especially high up North and in the mountains.

Maps showing the share of people with disabilities and the combined share of PWDs and seniors in California, with recent (2019-23) large fires. Seniors and PWDs are concentrated in many fire danger zones in the state.

Looking at the LA area and recent (2024-25) fires, Altadena and areas around Ventura County fires had somewhat high levels of disability, but Pacific Palisades had a relatively low share. The combination of seniors and PWDs, though, placed one Altadena census tract and all of Pacific Palisades in the top decile of California census tracts: in the Altadena census tract closest to the hills, 31% of the population is senior and/or disabled, while tracts in Pacific Palisades are 32% and 38%. (Census tracts for Malibu, which is under threat from the Palisades Fire, are in the top 2 deciles for the combo of seniors & PWDs; the Santa Monica tract closest to the fire is the one with the highest rate in Santa Monica).

In the LA area, PWDs live in some hillside and mountainous danger areas; the more concerning map is the combination of seniors and PWDs, where rates are high in dangerous parts of Ventura County, around the Palisades fire footprint, and at the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains -- including where the Eaton fire is burning

I also looked at the Bay Area and the LA basin compared to perimeters for historic fires since 1950. In the Bay Area, seniors and PWDs have a large presence in the fire-prone mountains of Sonoma, Napa and Santa Cruz counties, with another group among fire prone grasslands in Solano County (the North Bay has some of the cheaper housing in the nine county Bay Area, so this makes sense). Zooming into the central Bay Area, the fire prone Berkeley and Oakland Hills – including the census tract that touches the footprint of the 1991 Oakland Hills fire – have a relatively high chunk of seniors and PWDs, and the North Berkeley Hills have the highest rate of combined seniors & PWDs in that city.

In the Bay Area, seniors and PWDs are highly concentrated in the flammable North bay, while there are also high combined rates in some hillside communities along the San Mateo County coast, near Santa Cruz, and in the Berkeley and Oakland Hills.

The LA area historical map is harder to read due to the overwhelming number of fires there since 1950, but there’s a pretty clear trend that seniors & PWDs disproportionately live in many fire-prone areas. Check it out for yourself.

Many fires since 1950 have burned in the areas that now have a high concentration of seniors and PWDs. Image descriptions: maps of LA County with footprints of historic fire perimeters.

Safer in the City Center

Looking at these maps, I can’t help but also notice two places with especially high rates of disability that don’t have big fire risks. Three census tracts in downtown Oakland have rates of disability 24% or higher; downtown SF and the Mission District feature 15 tracts above 24%, with six Tenderloin tracts at or above 34.9% disabled and one clocking a 48.4% disability rate. Those are census tracts with double, triple, or even quadruple the statewide average (11%), and they are in urban centers shielded from wildfire risk. The presence of relatively affordable multifamily housing make those places livable for PWDs; even if there are some downsides, they don’t include fast-moving flames with difficult evacuations.

Ultimately, we need more locations like those in SF and Oakland: dense, urban, transit-friendly environments that are far from climate risks and allow us to live more sustainably. California’s mistakes show how misguided policies can push Californians, and especially seniors and PWDs, into wildfire danger zones. Hopefully we can fix our policies to transform where and how we live, thus saving lives.

(And yes, we always need to improve our disaster response strategies – but that’ll be an easier task with a better urban form).