How Berkeley's NIMBYism Betrayed the Disability Rights Movement: Part 1

Berkeley is the home of the modern disability Rights movement. But anti-housing activism in the '60s and '70s made the town inhospitable to people with disabilities...

Berkeley is the home of the modern Disability Rights Movement.

… But anti-housing advocates and policies made the city inaccessible to many people with disabilities

Census data presented below comes from the IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS), referencing the decennial census from 1940-2020

In the 1960s and 1970s, Berkeley, California was a hotbed of activism. In addition to the well-known anti-war and Free Speech movements, two others loomed large: the modern Disability Rights Movement and the "Not In My Backyard" (NIMBY) movement. The Disability Rights Movement started in Berkeley itself, proudly proclaiming that people with disabilities (PWDs) deserve to live in the community and pursue education, employment, and self-determination. The Independent Living philosophy that grew in Berkeley laid the foundation for decades of disability activism and progress across the globe. But then, the NIMBY movement said that there were too many homes being built in Berkeley, and too many people wanted to live there. NIMBYism put the brakes on development – and made it so every time someone with a disability says "I want to live independently in Berkeley," the Universe replies, "good luck finding a place."

This is the first in a 2-3 part series on Berkeley, the disability rights movement, and how anti-housing policies have made the "Home of the Modern Disability Rights Movement" physically and financially inaccessible to so many people with disabilities.

Part 1 will cover the background of disability rights in Berkeley, the anti-housing backlash that started in the 1960s and accelerated in the 70s; and impacts on the housing stock and population from 1940-2020; and changes in the disability population from 1970-2020 (the census didn't feature disability data from 1940-1960).

Part 2 (and maybe Part 3) will cover the age & building sizes of Berkeley's housing stock and implications for accessibility, looking at trends over 10 years of census data; the makeup of Berkeley's disability population; and broader impacts for people with disabilities in and outside of Berkeley.

Time to dig in!

Berkeley births the disability rights movement

In 1962, Ed Roberts was admitted to the University of California, Berkeley. The 23-year-old had acquired polio in his teens and was paralyzed from the neck down (aside from wiggling a couple fingers and some toes). After finishing high school from a mix of home and institution, he was accepted to UC Berkeley – but Roberts and his mother, Zona, had to fight with certain administrators and the California Department of Vocational Rehabilitation for him to be officially enrolled. The criticisms they faced ranged from vague statements that “we’ve tried cripples before and it didn’t work” (said by one of the Berkeley Deans) to worries within Vocational Rehabilitation that he’d be unemployable and the education would be a waste. Still, Roberts and his mother persisted, and he eventually moved into an empty wing of the University’s Cowell Hospital – the only campus facility that could handle his 800-pound iron lung – with Roberts’ stipulation that it be treated as a dorm space and not a medical facility.

The following years cemented Roberts as the "father of the modern disability rights movement." Berkeley was the movement's birthplace and became a major center of disability leadership through the decades.

Soon after Roberts enrolled in '62, other students with physical disabilities joined and developed a strong advocacy mindset. The self-labeled “Rolling Quads” fought for inclusion, access and services in the school and the city at large. Berkeley soon had the nation’s first curb cuts and the campus Physically Disabled Student’s Program (PDSP) was the first student-run program of its kind. The Rolling Quads began developing the early seeds of the Independent Living Movement with the idea that people with disabilities (PWDs) could live independently in the community with appropriate supports, like housing modifications and personal attendant care.

Over the years, the PDSP became a formal, staffed administrative office called the Disabled Students’ Program (DSP). The University also created, maintained, and eventually (unfortunately) disbanded a Disabled Students Residence Program (DSRP) that taught independent living skills to freshman and transfer students; for those that needed it, the DSRP provided attendant care for one semester, helped students enroll in In-Home Supportive Services (a Medi-Cal-adjacent program that pays for personal attendants), and taught students to hire and manage their own attendant team. UC Berkeley eventually developed a Disability Studies minor and became known for its myriad disability-focused groups and activities. For this reason, the school has been a bit of a destination for qualifying students with disabilities for decades.

As more students with disabilities arrived in Berkeley and developed an independent living philosophy, they recognized a need for services beyond UC Berkeley as well. Students partnered with community members (including recent Berkeley grads with disabilities) to found the Center for Independent Living, a transformative nonprofit that provided services and referrals to the community, in 1974. Disability advocates from across the state – and even the country – gravitated to the city and it became a major hub of activism with national implications. The CIL model was replicated nationwide, while Berkeley was a key organizing hub for disability rights legislation like Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1974 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990.

Berkeley's disability resources are some of the best in the country. In 1998, Berkeley residents voted on a small city tax to fund on-call accessible transportation and backup attendant care for residents with disabilities – a set of services I can’t recall seeing in any other city (but please let me know if similar nonprofits exist elsewhere!). There are now a wide variety of disability-focused nonprofits and groups and activities, many housed in the universally-accessible Ed Roberts Campus office complex and community center. Indeed, for PWDs lucky enough to live in Berkeley, it provides a tremendous quality of life. The weather and transportation networks in the Bay Area, the open-minded nature of the SF-Berkeley-Oakland trifecta, and California’s relatively generous social services are yet more reasons why Berkeley is such a disability destination.

There goes the neighborhood: Housing wars, downzoning and city-wide impacts

But something else happened in Berkeley that’s betrayed that legacy and made the city inhospitable to PWDs: it virtually stopped adding new housing and even destroyed many single room occupancy (SRO) units downtown. Now, this next section owes a lot to Darrell Owens’s fantastic History of Gentrification in Berkeley (Part I and Part II). The pieces are well worth the read if you have the time, and this section recaps Owens' work with some of my own thoughts and graphs and links. (I should also note that Owens addresses gentrification through an economic and racial lens with a spotlight on displacement of the African-American community; that’s relevant for this blog since there’s a higher rate of disability among African-Americans than among the rest of the population).

Founding-1960s

As Owens explains, Berkeley is the home of single-family zoning – a legal code which makes it illegal to build anything but a single-family home on a given plot of land. The first neighborhood to adopt single family zoning the Elmwood district in 1916, but it quickly spread to much of the rest of Berkeley. This single-family zoning model was developed to support de facto economic segregation and make racial segregation (e.g., through redlining or neighborhood covenants) easier. But despite widespread single-family zoning in the city, there was still decent housing and population growth through the 1950s and early 1960s. That included large growth of the city’s Black population and, on the housing front, growth of cheaply-built “dingbat” apartments starting in the 50s.

The transformations irked many parties, from segregationist racists worried about neighborhood integration to tenants’ advocates that considered dingbat development to just be churning out low-quality housing for renters. In response, the 1960s and 70s featured a slew of anti-development policies and interesting alliances. The first wave of policies came in the form of downzoning in neighborhoods that had seen growing Black populations. Later stages of downzoning were backed up with arguments that equated apartments with blight and espoused the environmental benefits of green space and low density over “soulless” dingbat apartments.

The dramatic zoning changes saw some neighborhoods drop from R-4 (multifamily/6-story-max) to R-1 (single-family) zoning and others go from R-5 (high density/six-story) to R-2 (duplex) zoning. Suddenly, the city changed its maps to disallow potentially hundreds of thousands of new homes that could otherwise be built with denser zoning. Still, the 1960s saw modest growth because rezoning was a gradual process that took time to slow development – and since many projects were already in the pipeline and couldn’t be canceled or blocked. But sure enough, construction cratered in the second half of the decade. Other Bay Area cities followed suit in pursuing widespread downzoning but kept welcoming job opportunities, especially in San Francisco and the Peninsula. Rents rose across the region, but as Owens breaks down, the impact in Berkeley was more dramatic and led to significant displacement of Black renters into Oakland especially.

Disability note: due to their design of having housing above a garage, dingbat apartments are not accessible for people with mobility disabilities. Large apartment complexes tend to provide the most accessible housing, but those were virtually outlawed in the NIMBY backlash alongside dingbats. I'll cover the nature of accessible housing in Berkeley more in-depth in subsequent posts.

1972-1990s: the Shrinking City

The late 1960s and early 1970s ushered in a revolutionary wave of sorts in Berkeley, including the well-known fight over People’s Park (a stalled university construction project that was taken over by community members and transformed into a park, when a violent crackdown from the National Guard raised its profile further). In the face of rising rents, tenants’ groups and Socialists passed a rent control ordinance in 1972, but that was struck down in 1973. Also in 1973, a coalition of anti-development left- and right-NIMBYs put the transformative Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance (NPO) on the ballot, and it passed in 1973.

The two primary authors of the NPO were an anti-density homeowner named Martha Nicoloff and a leftist tenant activist out of UC named Ken Hughes. The homeowner/leftist alliance that created the NPO was a microcosm of the larger neighborhood-centric political coalition which became the backbone of Berkeley Citizens Action throughout the 1970s.

From Owens' Part II:

The spirit of the NPO, as written by Hughes, was to give the working class flatlands the same anti-development zoning as the single-family zoned wealthy hills. Beyond the primary authors, the NPO was largely drafted and politically organized around by leftists and tenant groups and much of its advertisements used anti-speculator rhetoric. The NPO also appealed to tenant activists because high density zoning had allowed some landlords to flip older apartments into new high rent complexes. The proponents also argued to homeowners that the additional population from dense housing imposed higher taxes on them.

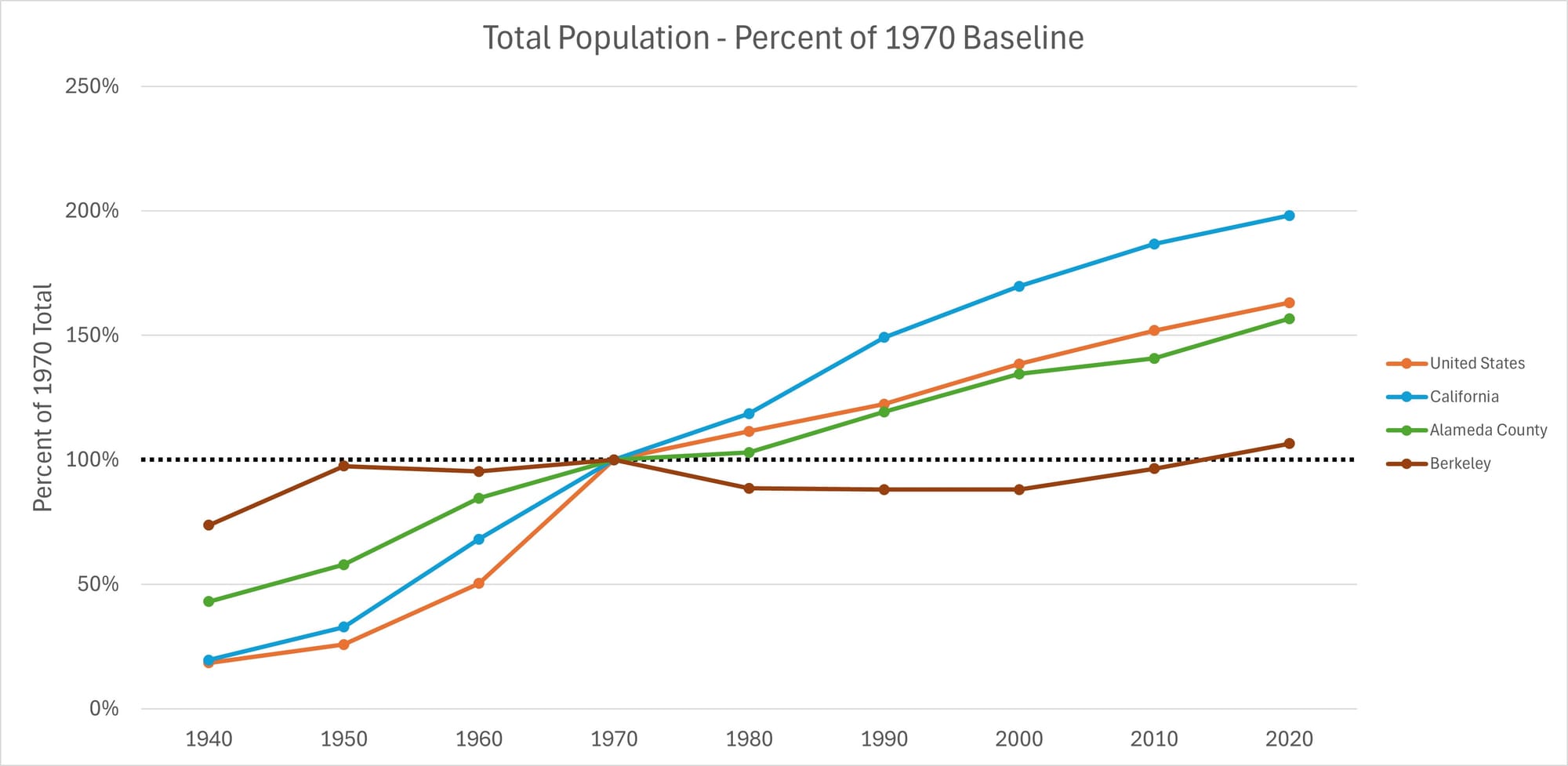

Combined with the widespread downzoning in the city, the NPO’s onerous requirements essentially halted new construction in Berkeley for decades. In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the city lost significant housing through a mix of shuttered single-room-occupancy (SRO) hotels and landlords converting multi-unit properties into larger single-family units for sale. Essentially the only construction of new homes in the 1970s and 1980s was in single-family zoned areas and especially in the hills – a location with good views, for sure, but also car-centric and with fire and other emergency risks. Berkeley had a drop in the total number of housing units and its total population in those two decades. The population loss was disproportionately low income, renters and Black folks; however, as Owens notes, one population did grow in those years: the unhoused population.

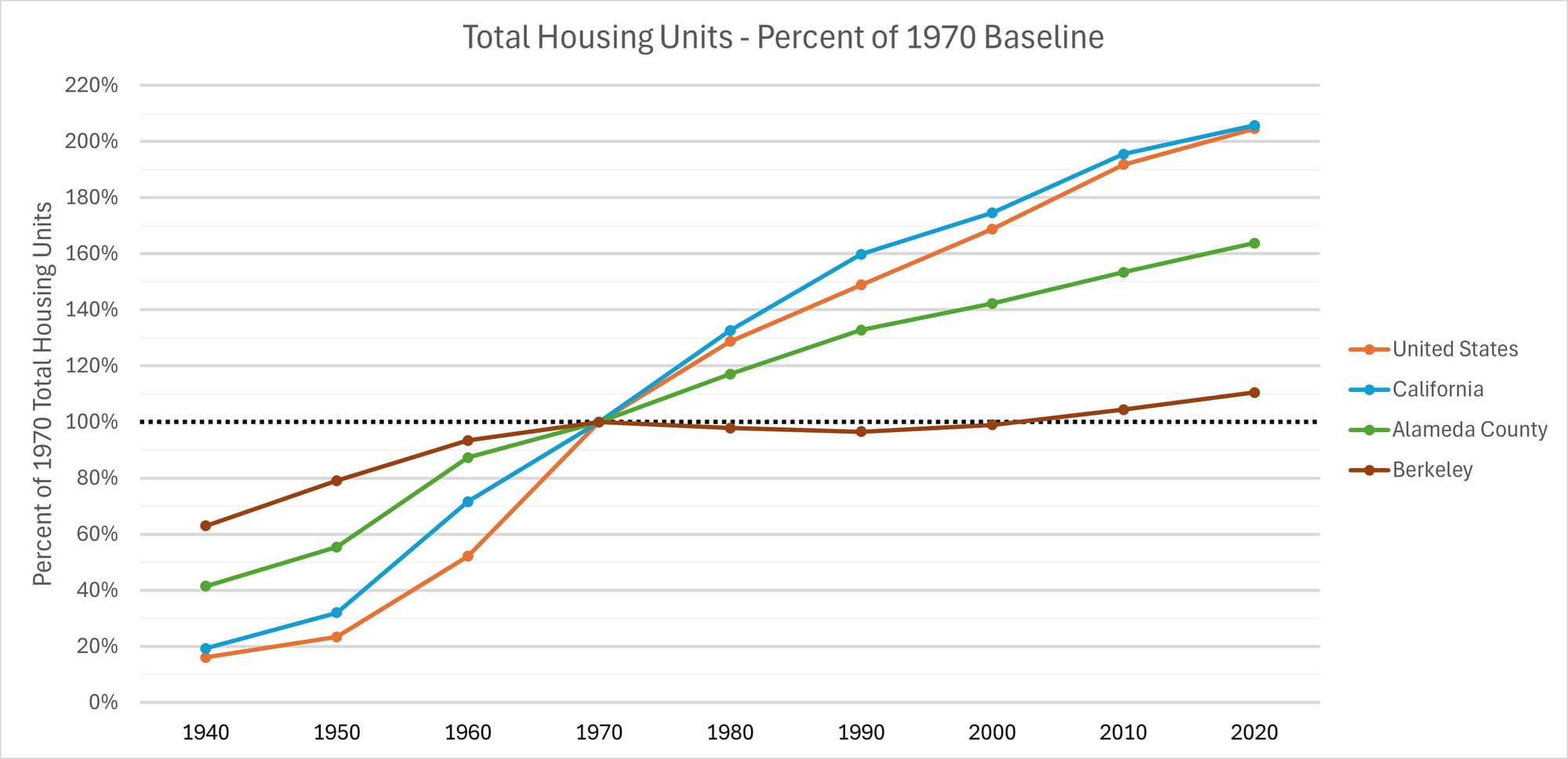

Now, housing growth slowed significantly between the 1950s (18.0% growth) and the 1960s (7.1% growth). But per the decennial census, 1970 is a clear inflection point where the city began shrinking. From 1970 to 1990, Berkeley lost 3.4% of its housing stock and a whopping 12% of its population. It stands in stark contrast to Alameda County, which had 32.7% more homes and 19.2% more people in those two decades; the state grew even more, with 59.8% more homes and 49.1% more people. Whatever extra people could have been housed in Berkeley if it kept growing at a healthy clip ended up living elsewhere, whether that was Oakland or Stockton or Arizona; some people who could have been housed ended up on Berkeley's streets instead.

Housing units and population as a % of the 1970 baseline: USA, CA, Alameda County & Berkeley

Owens ends his piece talking about new development in the 1990s onward, sparked by a series of neighborhood-specific rezonings starting with downtown. The first multifamily building that went to City Council was the Gaia Building (now called Sterling Allston) in 1998, which at the time was “the first privately funded housing in the downtown core since at least World War II” according to the San Francisco Chronicle’s coverage. This disability tidbit is telling:

The fight finds feminists and spiritualists siding with [building developer] Kennedy, who also claims the support of advocates for the disabled and mass transit. The building would be fully accessible to those with disabilities, and Kennedy even promises to provide electric cars that tenants can share to do their errands.

…

Kennedy said his critics are a few "NIMBYs" and "career obstructionists," while supporters "come from all across the community."

"The people lining up behind it (the project) are environmentalists, affordable-housing advocates, accessibility promoters, transportation planners and mass transit promoters," he said.

That’s right – some of the biggest advocates for the new, 108-unit, seven-story building were PWDs. When you look at the long-term impact of NIMBYism on the accessibility of Berkeley’s housing stock, their advocacy makes perfect sense. Berkeley’s largely prewar housing had plenty of stairs and narrow doors and halls; dingbats were inaccessible too. At the time the Gaia Building was proposed, the Americans with Disabilities Act (which applies to common area accessibility) and Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 (FHAA) (which applies to unit accessibility and tenant accommodations) were less than a decade old and applied to new apartment buildings. [Note: the Gaia Building is not “universally accessible,” but its apartments worked for many people with disabilities and were a huge access upgrade over Berkeley’s older buildings]. A new building with far better accessibility than other Berkeley housing, great transit access, and a significant chunk of income-restricted affordable housing was a slam dunk for the disability community.

The Gaia Building was eventually approved, albeit after a very long meeting. It ushered in a new era of development in the city that, while welcome, still couldn't keep pace with demand.

1990s-2020: Growth, but not nearly enough

From the 1990s through the 2010s, Berkeley was still painfully slow at adding new housing stock. The same active minority of NIMBYs that fought the Gaia Building never relented. They used every tool of obstruction that state and city governments allowed, from voicing loud opposition in large numbers at city meetings to filing bad faith environmental challenges under the California Environmental Quality Act. In some cases, NIMBYs have outright blocked developments. In others, they’ve been successful at shrinking the size of proposed buildings. And in virtually every case, they try to drag out the process, denying much-needed housing in the interim even when things do reach the finish line. The lengthy and expensive development process, combined with the uncertainty over whether a proposal could even make it through the maze of commission and city Council meetings necessary to win approval, meant that some developers who might build housing in Berkeley avoided it entirely. Developers that have tried all understand that they’ll need to pull in high rents to make it worthwhile.

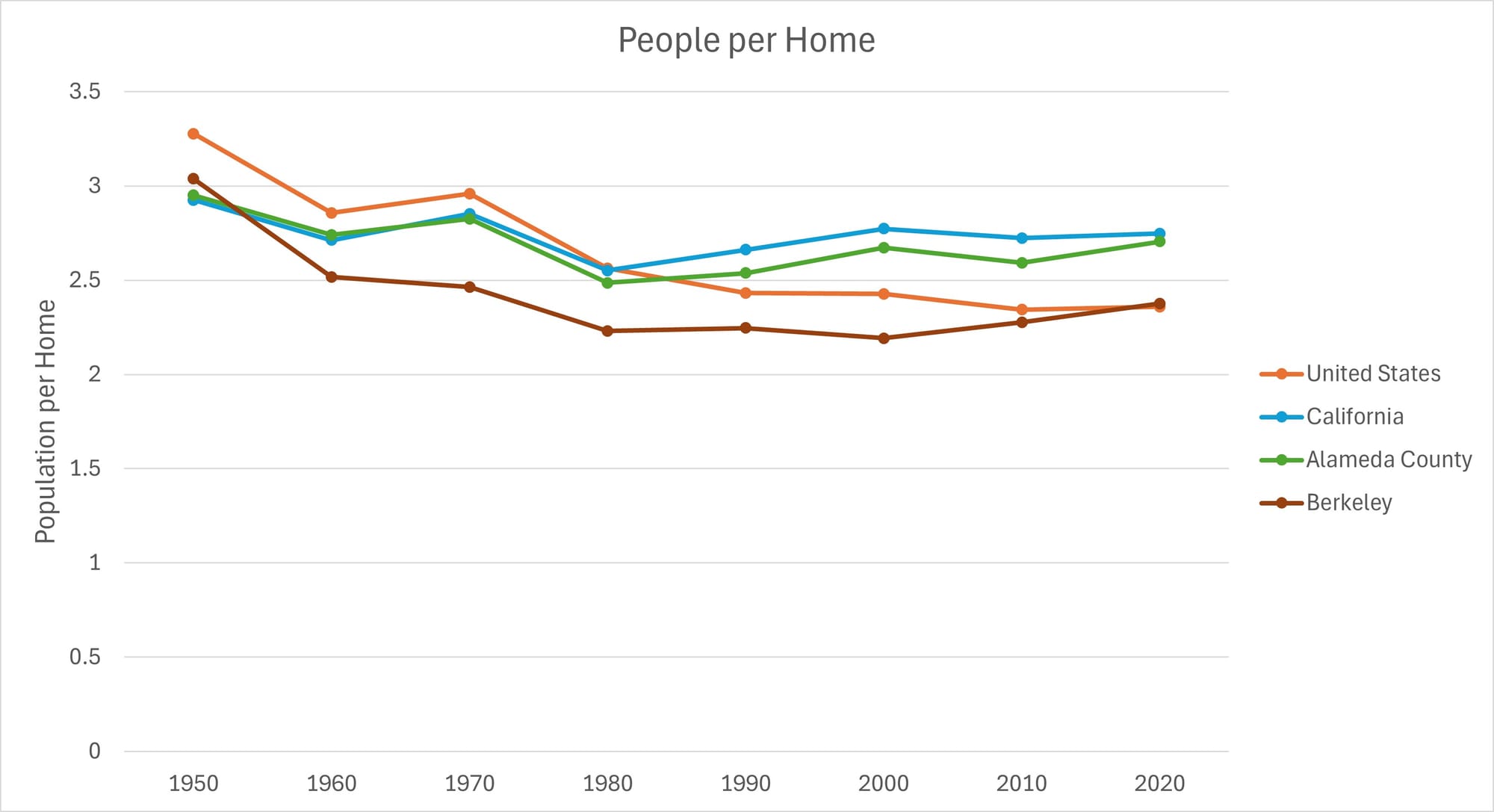

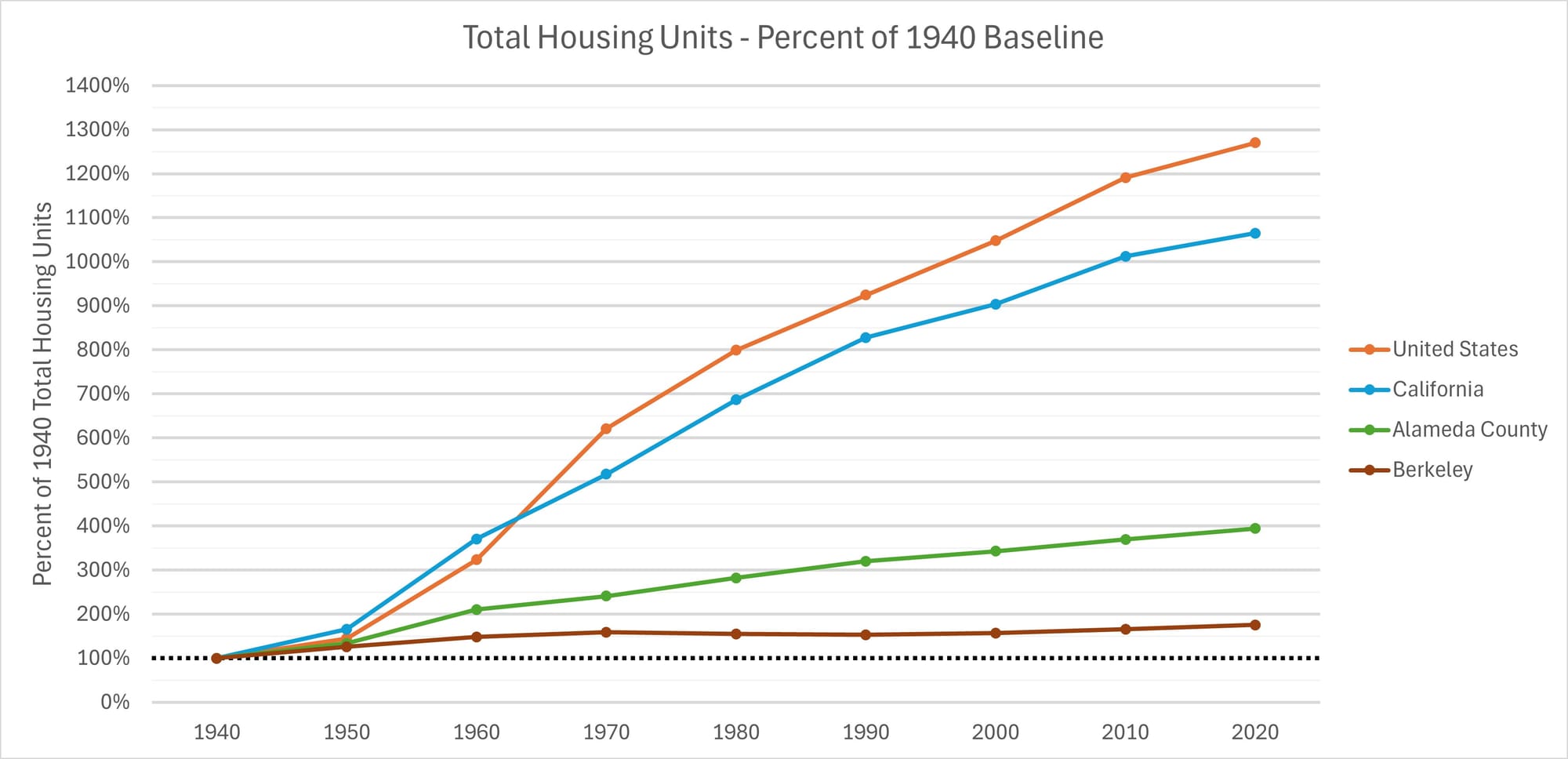

Between 1990 and 2020, Berkeley’s housing stock grew by a total of 14.4% (4.6% per decade) – much lower than the growth of Alameda County (23.4% or 7.3% per decade), California (28.7% or 8.8% per decade) and the US as a whole (37.4%, or 11.2% per decade). Things have sped up in the past decade or so: the 2010s, with 5.8% growth, was Berkeley’s best decade since the 1960s (7.1%), yet far behind the growth of the 1940s (25.6%) and 1950s (18.0%). But the 2010's' housing growth wasn't enough to keep up with population growth (10.4%): the 4.1 people per home added in the 2010s was even worse than the 3.8 figure in the 2000s. As Owens notes, Berkeley's inadequate housing growth drove overcrowding, high prices and increasing homelessness in the city – a trio of problems that disproportionately impact PWDs.

People per home, 1950-2020

Digging out of the Hole:

Development has accelerated this decade due to the delayed impact of gradual rezonings, growing local-level activism by pro-housing groups and their allies, and a series of state-level laws that have taken away or significantly dulled the tools that NIMBYs use to block housing. There are now several 200+ foot tall buildings, multiple shorter towers and plenty of mid-rises in the construction pipeline; due to zoning, the especially tall buildings are concentrated downtown and on Southside, with mid-rises in those two neighborhoods and on commercial corridors. Both North Berkeley and Ashby BART stations’ parking lots are set to be redeveloped into mid-rises, though the proposed developments are shorter than many advocates wanted (and will accordingly have far fewer units). The developer-pipeline blog SFYIMBY.com keeps track of proposed and under-construction buildings in the city and is worth a look (note: that website isn’t affiliated with the SF YIMBY nonprofit, which ends in .org).

Buildings in Berkeley's pipeline:

Image descriptions: 1) a Google Earth view of downtown Berkeley & Southside in its current form, with a mix of single-family homes, duplexes, and mid-rises plus a few under-200 foot towers downtown; 2) the same image with renderings of the proposed developments, including plenty of mid-rises and a few towers, with several over 200 feet and one over 300 feet; 3) a zoomed out image of the whole city with proposed developments, showing that developments are concentrated on a few neighborhoods and commercial corridors, with most of the low-slung city completely untouched

The future is less certain. There are reasons to be optimistic. Just this year, Berkeley achieved a couple milestones by eliminating single-family zoning citywide (now allowing 2-4 units on previously single-family zoned areas, depending on location) and electing an outsider, pro-housing mayor, who just beat a more NIMBY-leaning councilmember. There is certainly momentum toward Berkeley rapidly developing and making up for its housing shortage, plus improving its roadways and transit networks to be better for folks who can’t drive. To be clear, parties continue to fight new housing, as well as infrastructure investments that could improve quality-of-life for PWDs. NIMBYs will pull what levers they can to block or slow development, and we’re lucky that state-level reforms have taken some levers away. Berkeley is also subject to forces beyond its control, such as the movements of the Bay Area housing market or changing interest rates or whatever Donald Trump’s plans will do to the construction industry. But the pandemic-era construction boom is transforming downtown – all we can do now is fight for more and hope for the best.

The constraints of downzoning, the NPO, etc. have ultimately prevented Berkeley from reaching its true potential as a city. Berkeley is a great city in an awesome location with loads of amenities – and it could be even better with more density, letting more people call it home. If it had just grown at the same rate as Alameda County since 1940, Berkeley would have tallied more than 311,000 people and almost 118,000 homes in the 2020 census, instead of the real-and-underwhelming 124,321 people in 52,331 homes. Berkeley could easily be double or triple its current size, but a mix of slow growth and shrinkage since 1950 made it half-small-city, half-dense-suburb. Even now, its construction "boom" is limited to a few neighborhoods and corridors; instead of serving a vibrant mix of tenants, it's mostly tackling the immediate, overwhelming student housing shortage; and the single-family zoning reforms won't achieve Berkeley's full potential the same way more aggressive upzoning could. Berkeley's constraints will continue to weigh on it: even if there's progress, it'll be less than it could have been.

Housing units and population as a % of the 1940 baseline

Gentrification hits PWDs: 1970-2020

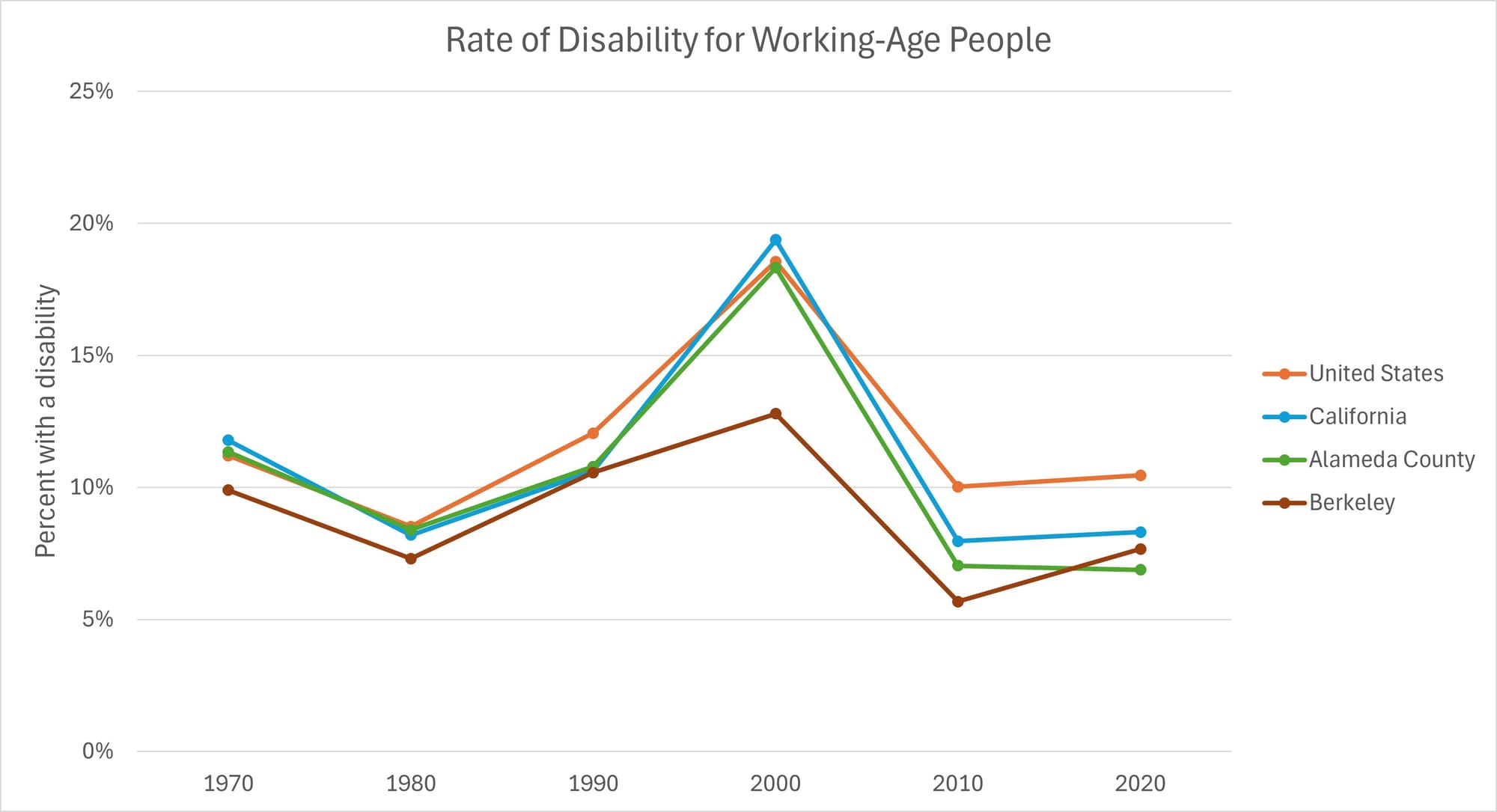

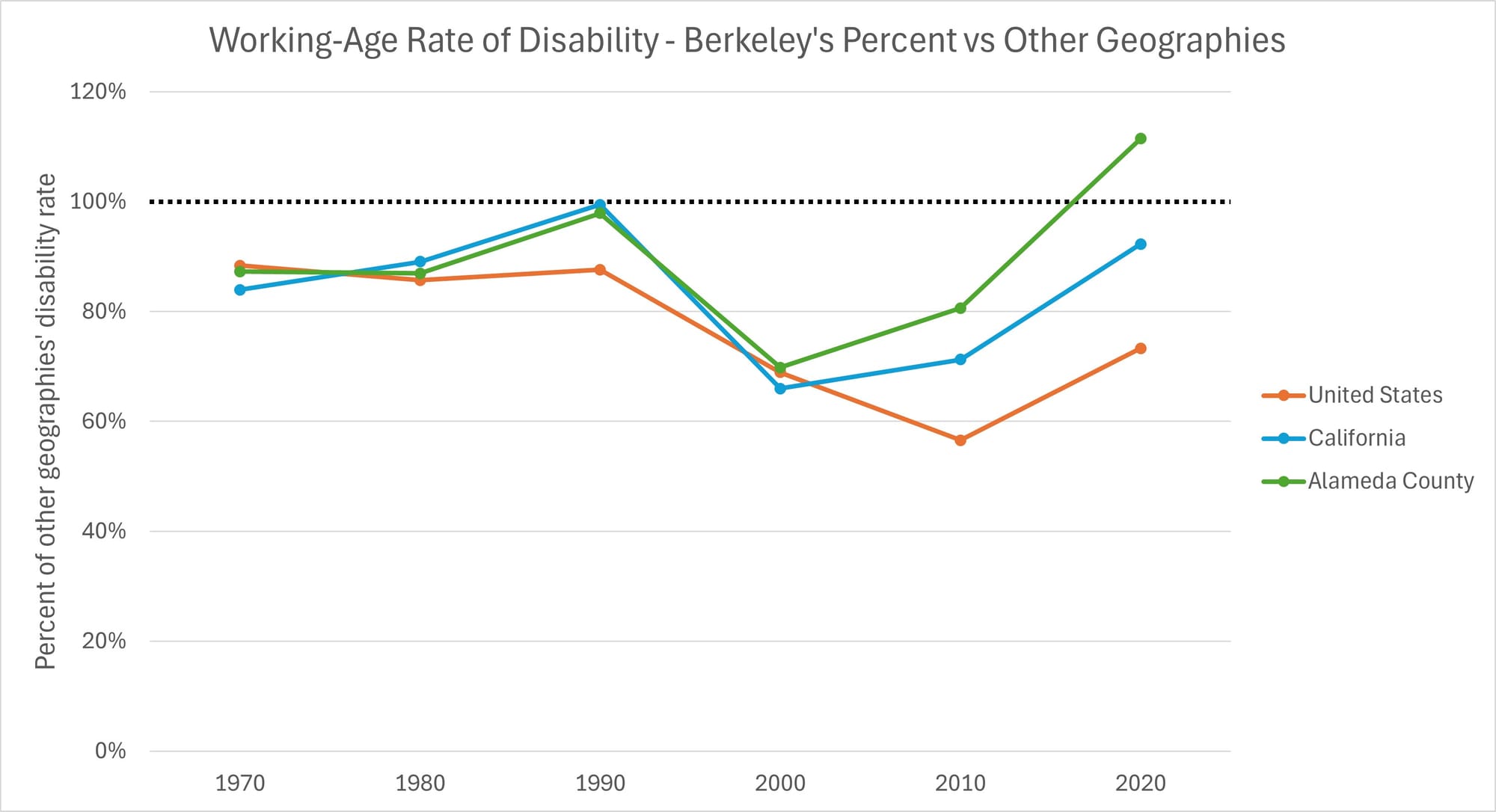

Berkeley's combination of high housing prices and limited accessible options has kept its rate of disability lower than the county, state, and national averages for almost all recent history. It's difficult to track disability data decade-by-decade, as the census's definition of disabled adults changed through the years – so, I compared rates of disability in the working-age population (16-64 or 18-64, depending on the census year) in Berkeley to rates in Alameda County, California, and the US as a whole. It shows a city that's failed to live up to the promises of the Disability Rights Movement, with a huge loss of PWDs by 2000-2010 that's just started to rebound.

1970 was the first time the Census tracked disability. That year, Berkeley had a disability rate (9.9%) that was lower than rates in Alameda County (11.3%), California (11.8%) and the US (11.2%). That means Berkeley's disability rate was roughly 87% of Alameda County's, 84% of California's and 88% of the country's rates. The rate actually increased by 1990 in comparison to Alameda County (98%) and California (99%), but stayed around 88% of the national average. By 2000, though, the floor had fallen out: Berkeley's rate of disability was 70% of Alameda County's, 66% of California's, and 69% of the country's rate of disability. In 2010, it was just 57% of the national average! By 2020, for reasons I'll brainstorm next time, things started to rebound: Berkeley actually climbed above Alameda County (112% of the county's rate), but still was behind California (92%) and well below the United States (73%).

Rate of disability for working age people, 1970-2020: Census % and Berkeley's rate compared to other geographies

If Berkeley's rate of disability had been higher, that would've represented likely tens of thousands of people with disabilities over the decades that could get to experience Berkeley's amenities, services, and disability community. But as happened with the Black community that's the focus of Owens' piece, many PWDs ended up living elsewhere, with consequences I'll dig into next time…

What comes next

That’s the rundown of Berkeley’s disability and housing history. Part 2 (and a possible Part 3 if things run long) will dig into the following:

1) Berkeley’s housing stock today: age, building sizes, and implications for accessibility

2) “Which PWDs get to live in Berkeley?” in data and rough categories

3) Concrete consequences of NIMBYism for PWDs in and outside Berkeley

Thanks for following along – catch you next time!

DisabilitYIMBY is a reader-supported publication. If you'd like to support this newsletter, consider a paid subscription!